Ch. 5 Training Three Skills

Two Faces of Emptiness

In this chapter, three essential skills for reducing and ultimately eliminating suffering are introduced: discipline, concentration, and insight. Developed together, these skills can rise to great heights and, remarkably, bring a practitioner to the level from which liberation becomes possible. Each skill will be explained through a dynamic model of human life. A traditional estimate of the time required to bring the skills to the level sufficient for full liberation is provided at the end of the chapter.

5.1 The three skills as subdivision of the Eightfold Path

The meditation path toward liberation unfolds through different phases. The first cultivates inner strength, helping one become more resilient to stress and more focused in applying attention. It also frees one from habitual patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior that repeatedly pull the mind off course. Through further practice in the second and third phase, it is possible to release even deep-seated existential fear and dread. Overcoming these heavy burdens opens the way to genuine freedom and marks a profound step to further liberation.

Although these phases differ in aim, they all rely on the same three skills: discipline, concentration, and insight. These lie at the heart of the first major teaching of the Buddhadhamma, the Four Noble Truths, and form a different perspective on the Eightfold Path toward liberation. [Canonical source: SN 56.11, MN 140, and AN 3.33.]

1. There is suffering.

2. Suffering has craving as its cause.

3. The cause of suffering can be ended.

4. There is a path leading to that end.

The suffering intended here is of a particular kind. It refers to the existential anxiety and inner dread, what modern languages call Angst and spleen, discussed above. Ordinary worldly suffering, arising from illness, impermanence, or conflict, is not the direct focus of the Four Noble Truths. Rather, the teaching addresses the deeper unease that underlies all such experiences. Craving for specific things or situations, often mistaken as a means to escape both worldly and existential pain, only intensifies the first while leaving the second unresolved.

The Fourth Noble Truth, the Noble Eightfold Path, offers a practical way to end this suffering. It consists of eight steps: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. These can be grouped into the following three classes of training (Cūḷavedalla Sutta, MN 44).

• Discipline: right speech, right action, right livelihood

• Concentration: right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration

• Insight: right view, right intention

This is how the Pali Canon presents a threefold division of the path, framing discipline, concentration, and insight as the essential skills of cultivation.

A Medical Comparison

The Visuddhimagga (Ch. XVI, Sec. 87) frames the Four Noble Truths as a medical treatment for suffering. Unlike the division into three trainings, this metaphorical approach highlights the therapeutic function of the Dhamma.

1. There is suffering. This observation is the recognition of an illness.

2. Suffering has a cause. This is the diagnosis, the identification of a disease.

3. This cause can be stopped. This is the prognosis, with the possibility of a curing medicine.

4. The Eightfold Path describes a therapy.

Both perspectives can be brought together to illuminate the practice more fully. Here, the medical model is extended to cover the threefold division of the path.

• Discipline. This functions as hygiene, preventing further causes of illness.

• Concentration. This functions as symptomatic relief, sometimes needed for a real cure.

• Wisdom. This functions as a real cure, like an antibiotic.

• Liberation. This functions as a vaccine, making the person immune to that type of illness.

As mentioned there are several levels of liberation. In the metaphor these correspond to becoming immune to several types of illnesses.

The extended medical metaphor provides a clear and memorable picture of how the path functions as a therapy for suffering, illustrating both the Four Noble Truths and the three core trainings.

Regrouping of the Eightfold Path

For didactic purposes, we adopt a slightly different, functional subdivision of the Eightfold Path into three groups of training, placing right effort under discipline and right mindfulness under insight:

• Discipline: right effort, right action, right speech, right livelihood

• Concentration: right concentration

• Insight: right view, right intention, right mindfulness.

Discipline forms the foundation, combining restraint that withholds what leads astray and effort that promotes what leads onward. Concentration unifies the mind, steadying attention with clarity and composure. Insight does not arise through intention but emerges from the openness of concentration and the alertness cultivated by discipline.

5.2 Use of the three skills

The life of a member of Homo sapiens, for instance your own, may be viewed as a continuous stream of actions, impressions, and mind-states. Let us begin with an action that has just been performed. Such an action may occur through the body, through speech, or within cognition itself. Each act alters either the surrounding world or the contents of the mind. This alteration, in turn, becomes new input, giving rise to a corresponding mind-state: a readiness or inclination to act in a particular way. That mind-state, together with the fresh input it accompanies, conditions the next action. The cycle thus perpetuates itself moment by moment. This account is a simplification of the principle of dependent origination, inspired by the Abhidhamma teachings of Dr. U Nyandamalabhivamsa.

To understand this figure, imagine yourself in the driver’s seat of a car. Before you are many instruments. They fall into two distinct groups. Some can be activated: the accelerator and brake pedals, the horn, and the switches for lights. Let us call these the action controls. Others can only be observed: the speedometer, the mileage counter, and the warning lights. These provide input, or in another sense, results. What appears on the dashboard is the outcome of earlier choices and movements. As the driver, you decide what to do next, partly in response to these results and partly to the behavior of the surrounding traffic. The driver therefore occupies the position between resultant input and action.

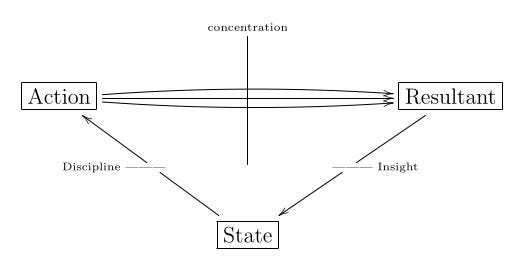

Now shift the image from driving a car to the stream of human experience. In a similar way, the flow of consciousness in Figure 5.1 contains three elements: Action, Resultant, and State. The State corresponds to the driver’s role of making decisions. After each action—whether through body, speech, or mind—the experienced world changes. A bodily action alters the physical surroundings and produces new sensory input. Speech modifies the social environment and evokes responses. A mental action does not move matter, but it reshapes attention and thought. In every case, the result of action becomes new input for the state that decides what follows.

The stream of consciousness is therefore composed of a continuous sequence of moments drawn from these three fundamental sources: Action, Resultant, and State, which correspond to doing, experiencing, and intending. Intention is the central function of the mind-state that selects the next action. The clockwise flow

Action → Resultant → State → Action → Resultant → …

represents the causal chain of events. This is not always the order in which we perceive them, because part of the process remains hidden from awareness. The Buddhadhamma calls this obscured portion ‘ignorance’. If awareness were complete, as said to be the case for an Arahat, a fully enlightened person, the logical sequence of causes and effects would probably coincide with the way experience is lived.

Why does a human being so often suffer? When we receive pleasant or unpleasant input, we tend to react automatically: grasping at what pleases us and resisting what does not. These reactions give rise to desire and aversion, which are unwholesome mind-states. They in turn lead to unwholesome actions that produce in both cases unpleasant results, reinforcing the tendency of aversion in the next state of mind. Suffering arises through this loop of reaction and result, a self-sustaining pattern of dependent origination. This shows how the conditioning of the mind with desire and aversion perpetuates painful experience.

The possibility of freedom from this cycle is shown in Figure 5.2, through the three skills that enable a gradual transformation of the stream of consciousness and open the way toward liberation. The loop can be interrupted through the cultivation and application of concentration, insight, and discipline, that offer a way to change this flow.

Concentration helps weaken the seductive or painful pull of input by allowing us to redirect attention. By focusing on something neutral or skillful, we reduce the input’s emotional impact.

When input is still experienced as pleasant or unpleasant, mindful observation, foundational to insight, can prevent it from triggering a reactive mind-state. Mindfulness allows us to see the input clearly without immediately falling into desire or aversion. This a second possibility of improvement. At times, however, mindfulness may be too weak, too slow, or altogether absent. In such cases, the mind-state may still contain some unwholesome factors, and we may feel compelled to act in unwholesome ways.

If this happens, discipline, especially ethical discipline, comes to our aid. It helps prevent harmful action, even when desire or aversion is present in the mind. This restraint is a third possible interruption of the cycle.

5.3 Mutual development of the three skills

Discipline consists of ethics and of diligence: on the one hand respectful behavior and on the other remaining active in a certain direction. It is developed using the right effort. For this right effort one needs some motivation. That can be curiosity, or can be based on some form of confidence, after one has heard or read that the practice can bring solace. The strongest motivation comes from personal experience that the method works.

Concentration consists of keeping attention in a certain direction. It is developed by repeating. One invites the attention to rest upon the experience of the breath cycles. For one cycle of breath this is not difficult. If that attention drifts away, then one usually does not immediately recognize this fact, but only some time after. At that point of recognition, one relaxes and returns in a friendly fashion to observing the cycles of one’s breath. The student is asked to repeat this with patience many times.

Insight consists of correctly observing the phenomena that come to us, and notably to have an intuitive knowledge whether these are wholesome or not. It is developed by extending the previous exercise. One pays attention to the cycles of breathing, but if one forgets this and pays attention to something else, then one is asked to observe the ‘visitor’ for some moments and study intuitively its nature. This in order to prevent any unwholesome visitors to grow. For insight to occur, one needs a certain degree of concentration. But insight cannot be obtained at will. A friendly and patient attitude is important, as it is not known when insight comes. This is similar to insight into a problem in mathematics or physics, that may come in an unexpected moment, or even not at all.

Insight is the most important of the three skills. If insight is deep enough, and the factors of ‘letting go’ are present, this notion will be described in a later chapter, then realization, also known as liberation or enlightenment, may happen.

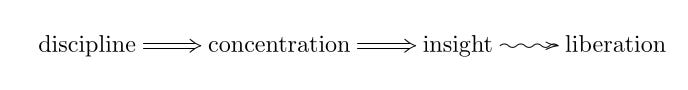

Summarizing, for the occurrence of liberation, one needs insight, for insight one needs concentration, and for concentration one needs discipline.

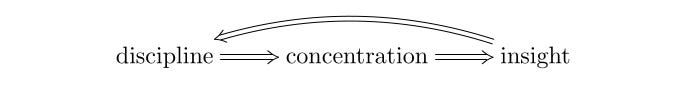

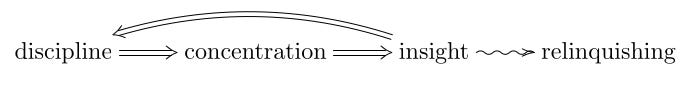

From this scheme one might think that discipline must first be fully developed, and only then concentration can follow, which in turn is followed by insight. But that is not how it works. You begin with a certain level of discipline. With that, you can reach a certain level of concentration, and then gain certain insights. These, in turn, strengthen your will and motivation to apply discipline in your meditation. With this increased discipline, you achieve stronger concentration and then greater insight. In this way, an upward spiral can develop with increasing levels of insight.

Then this process is repeated, with gradually higher levels of the three skills.:

In this way an upward spiral results. When a sufficient level of insight is reached, this may lead to the possibility of relinquishing, letting go, habit-loops.

As the habit-loops are hindering further development of insight, relinquishing them causes the spiral to rise further upward. Then, if sufficiently high, usually called deep, insight has developed, finally realization can occur.

The difference between relinquishing and liberation is that the first eliminates a particular habit loop, and the second eliminates a fundamental tendency, that underlies many habit loops.

As stated before, liberation does not happen at one level, but at four levels. These levels eliminate respectively 1. wrong view, the belief that self and the world are substantial, 2 and 3 aversion and sensual desire, and finally 4. pride. More unwholesome tendencies are eliminated during the four levels of liberation, but these will be mentioned later. The main point is that these more and more refined forms of liberation all are the fruit of practicing the three fundamental skills: discipline, concentration, and insight.

5.4 Time needed for realization

The work of releasing behavioral patterns and the driving tendencies behind them was traditionally done by monks and nuns. The reason is that deconditioning requires sustained effort, which is difficult to combine with the concerns of daily life. From this arose the “homeless ones,” the community of monks and nuns who lived together in monasteries under the guidance of a teacher, engaged in the work of deconditioning.

In the Theravāda tradition, monks and nuns go on alms round in the morning to collect their food, they eat, and after midday they no longer worry about getting food or eating, to be able to devote themselves fully to the practice. Alongside these contemplatives were the lay followers, who had work and often lived in families. As a result, they could devote less time to deconditioning their tendencies, and their progress along the path was slower. Since most in the tradition believed in rebirth, this was not considered a problem.

In our modern age, with its many conveniences, a new phenomenon has appeared: laypeople who can devote a considerable part of their time to meditation, both at home and during intensive retreats. In their meditative development, they can be compared to monastics. This explains the current flourishing of various forms of meditation, including insight meditation.

How much work is required to become completely deconditioned? According to tradition, the The Buddha himself spent six years in total, without having a teacher for the most important step. As an indication of how long it might take for someone who does have a teacher, he is said to have remarked the following (Satipatthana Sutta, MN 10):

It may take seven years.

Or seven months.

Or seven weeks.

Or even only seven days.

These are, of course, general indications. Much depends on one’s motivation and capacity. It is important to note that this capacity does not depend on intelligence. On one of my retreats, the following was said:

“In the time of the Buddha, there was a monk of low intelligence. He could not even remember the word ‘mindfulness’. Yet he succeeded in completing the path1.”

Stories like these I usually took as a form of mental encouragement.

Hello there Henk, you share great posts friend, I wanted to introduce myself, I’ve not been on Substack long!

Here is my latest article, it’s one I think you may enjoy:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/an-introduction-to-alchemy?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios