The advice in the previous Post 5 about the equipment needed on the path to liberation—discipline, concentration, and insight—was accompanied by a method for developing simultaneously these skills. The present post offers a global map, at different levels of resolution, of the terrain leading toward that goal. It should be emphasized that Posts 5 and 6 are preparatory. The actual practice will be described in the coming Posts 7, 8, and 9.

Even though everyone’s path to freedom looks different, a map can still be useful. This happens if we use a comfortable level of abstraction, making the points on the map stand for the general ‘there is craving’ and not for the exact form it takes, like ‘wanting coffee’ or ‘needing attention’. Let us follow the Buddhadhamma to explain this. Consciousness, at any given moment, consists of two aspects: an object (the content) and a state1. We call these consciousness moments. For example, when we look at a cup of freshly made cappuccino, the arising consciousness might be described as (cappuccino, s), where s could be liking, desiring, or disliking, depending on our disposition. Any path in our life is a stream of such consciousness moments. Of course, actions also matter. In the Buddhadhamma, actions are treated as a particular kind of object: the object of intention. Once the intention arises, the action is considered to follow automatically. So for a cappuccino lover, a short segment of their life stream might look like this:

(cappuccino, liking) → (intending to drink, desire) → (cappuccino gone, satisfaction) → (empty cup, wanting more)

When represented this way, our lives appear as highly personal streams of consciousness, shaped by the countless objects we encounter. But we it is possible to abstract away from the specific objects. Then the same sequence becomes:

liking → desire → satisfaction → wanting more

It is in this simplified space that the path to liberation can be described more generically. According to the Buddhadhamma, it is the state of consciousness, not its object, that is of primary importance on the path to liberation. People, at some point, will find themselves lingering in similar areas on the map, when focusing on the states.

A Hybrid Path

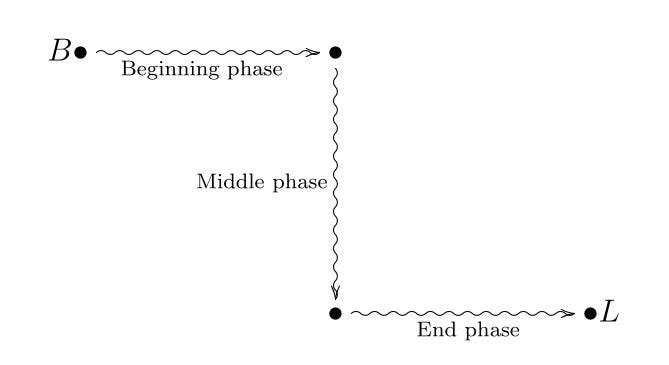

The path to liberation consists of three distinct phases2—beginning, middle, and end—each heading in a different direction. For this reason, we call it a hybrid path. In simplified form, the path looks as follows. Later more aspects will be added and the path drawn here will be part of a more wide hiking area.

The beginning phase runs along the initial motivation to meditate described in Post 3, with as goal to improve oneself by removing inner obstacles. The end phase runs along the ultimate path, with as motivation to transcend the self, that is, to develop a style of being beyond selfing: no longer constantly emphasizing “I, me, mine”. The middle phase serves as a transition between the first and end phases, during which one comes to understand that selfing is a continuous source for distress. Using a computer metaphor: in the beginning phase, one aims to improve the applications, to refine specific habitual patterns. In the end phase, the focus shifts to improving the operating system, to transform the underlying structure of selfing. The middle phase is the necessary transition, where one realizes that the system as a whole needs to change.

In everyday life, such hybrid paths are very common. Imagine arriving in a city by train and walking to your destination. The route seldom follows a single street; instead, it requires turns and a sequence of different roads. Though this may seem obvious, meditators may overlook it, since all "travel" happens on the same sitting cushion. But sitting is merely a vehicle, while the direction changes with each phase. Recognizing these shifts is essential, and is known in classical texts3 as the “Purification of knowledge and vision of what is and what is not the path.”

To explain and emphasize the distinct character of these three phases, we change the metaphor. Suppose we live in a cold climate in the Northern Hemisphere and plan as a holiday a hiking trip to a warm beach. We imagine the beginning phase of the journey as walking a substantial distance southward, gradually increasing the daily temperature. In the middle phase, we encounter a large mountain range, with weather marked by storms and atmospheric depression. There, we discover a tunnel, said to lead to the other side of the mountains where the climate is milder. After taking the tunnel, we emerge into improved weather, though still not perfect. In the end phase, conditions steadily get better as we continue toward our destination: a pristine, sunny beach.

In the Buddhadhamma it is said that the path is beautiful in the beginning, in the middle, and in the end. This means that although all three phases of the path come each with their own challenges, there are important moments of insight and release. Necessary is the readiness to face our suffering, so that we may ultimately transcend it.

Now we will describe in some greater detail what happens during the three phases of the path.

Beginning Phase

By practicing the threefold training the meditator will encounter the following regularly occurring cause of suffering. An external situation or inner thought or image may trigger an unpleasant feeling. This usually creates aversion and the wish to modify or escape that situation or thought. If this does not work, then the unpleasant feeling and reactions persist and the story tends to repeat itself. In this way a mental loop4 is created. If the attempt of modification or escape does work, then there may result pleasant feelings and a desire to be able regularly to deal with things this way. This will feed a different trajectory, and although it is pleasant, also this one is a repeating loop. These loops form patterns that shape our personality. In both cases the loops are forms of suffering, because of their ‘stickiness’, they cannot be stopped at will and limit the possibilities to pay attention to other things.

The three skills described in Post 5 enable the attenuation of such loops. They even can be released. By being aware of what happens for the entire duration of such a loop, one takes a distance. Then holding on to non-action, calmness, and awareness, it may happen that the loop dissolves. This way of relinquishing is also called disentangling, because many aspects of the loop need to be seen. Letting go sticky loops is a great relief. For some of the loops that have been with us for many years, the relief can be bigger than arriving later at the moment of liberation.

This kind of ‘work’, walking the path to liberation, is usually done in the context of a silent meditation retreat of 10 days or in a less intensive way during an eight-week MBI (Mindfulness-Based Intervention). One usually notices, however, that after the retreat or course, sooner or later the same or a similar mind-loop may reoccur. The reason is that within our mind linger the basic tendencies of desire, aversion, and ignorance. These continue to give rise to behavioral patterns, that become anchored as conscious or subliminal habit loops. After letting go an unwholesome loop, the underlying tendencies usually remain. Therefore the same pattern or a variant of it may return. This often is simply tackled by patiently repeating the work in the beginning phase.

A sustainable relief comes from the work during the later phases of the path. It is also possible to relinquish permanently the innate tendencies that form the cause of the unwholesome patterns of our personality. The obvious advantage is that the unwholesome patterns are not coming up again. But one needs to meditate longer, although not very much longer. So there is a choice here. Repeating regularly the shorter work of the beginning phase, or going through the middle and end phases. Meditators that make the first choice do this, so that they have more time to make improvements in the world in the style of Mahayana Buddhadhamma. Meditators that choose the second option go for permanent liberation in the style of Theravada Buddhadhamma. Actually, by dividing one’s time and attention, one can choose to develop in parallel permanent purification and improve the world.

Middle Phase

Insight versus Comfortable Ignorance

Our personality consists of a collection of patterns. These are essentially habit loops, that are available in varying degrees and form our style of being. Since some of these patterns involve suffering, the meditator is initially motivated to practice in order to relinquish them. Even partial success in this may bring a great sense of relief, though not a lasting one. The painful loops may resurface later, either during the retreat itself or sometime afterward.

If this happens, the reason is that these patterns are supported by deeper, underlying unwholesome tendencies. As practice continues, one begins to recognize these tendencies as desire and aversion. The temporary release from painful patterns often triggers a wish to continue the work and find a way to eradicate them in a sustainable manner.

At the same time, however, the ongoing relinquishment of patterns can evoke an eerie sense of loss, as if one is losing oneself. This creates an inner doubt: should one continue with the challenging work to relinquish unwholesome patterns, possibly uprooting the source of suffering, or cling to what is comfortable, but increasingly recognized as being unwholesome? Often, the insight that certain patterns cause suffering is hidden from the meditator, even when it's obvious to their friends. This phenomenon reflects a third fundamental tendency: ignorance, which conceals the unwholesomeness of some patterns. It may be this ignorance that prevents us from being ready to ‘make the turn’ that shifts toward the middle phase of the path.

Seeing through Virtual Realities

In most cases, this turn toward the middle phase of the path is not made consciously. More often, one simply slides into it. Then, suddenly, one finds oneself there, with a direct insight into the Three Fundamental Characteristics of Existence (3C): impermanence, non-self, and suffering. At that moment it becomes crystal clear that both the world and the self, previously held as solid and reliable ‘things’, are in fact Vitual Realities, made up in the mind. This is the first face of emptiness.

This deserves further explanation. Phenomena experienced from the outside—colors, sounds, scents, and so on—are grouped together in the mind to form what we perceive as the world. At the same time, there are internal phenomena: urges to drink or to eat, finding a way to do so, all with accompanying mind states. Also these are grouped together to form what we perceive as the self acting within the perceived world. The dynamic self and world seem to be stable, to continue as expected.

This is how we have grown up: as a self operating in a world. Both this self and world are taken for granted, as real and solid “things.” By contemplation, one may come to the conclusion, that these are not objective realities, but mental constructions. But meditation goes a step further, by having them experienced as mind-made Virtual Realities (VRs).

This stands in stark contrast to the previously held view, that self and world exist as solid entities. In the Buddhadhamma this is referred to as Wrong View. To find out that self and world are not solid entities is a dramatic discovery. We perhaps intuitively but certainly emotionally refuse to accept this. But clinging to the Wrong View in the presence of the 3C gives rise to a form of suffering, not caused by any external threat, but by eerie experiences, caused by the sheer unexpectedness of how things turn out to be.

Imagine a tribe living in a region with no history of earthquakes. One day, the earth quakes, not destructively, but enough to be seen and felt. No one is injured, yet the ground has rolled up and down beneath the people. That alone is enough to cause panic. Something one had assumed to be stable, the earth, turns out to be dynamic and unpredictable.

The insight obtained by the experience of the 3C means that not only the world is being perceived as unstable, but also the very self that perceives it. This will result in a simultaneous sense of derealization and depersonalization. The suffering that follows from this insight includes three interrelated aspects: anxiety, delusion, and disenchantment. One begins to see that these mind-states have long been lurking just beneath the surface for a long time, having been triggered at times when aspects of the three characteristics became apparent, such as when our plans unexpectedly failed. They were unconsciously present, like underwater currents, subtly shaping our experience and personality.

Urgency

This is the fundamental Lack, a sense that something is missing. It marks the First Face of Emptiness, implicated by the title of this book, and is the cause of suffering implicated in the second Noble Truth of the Buddhadhamma. The good news is that this existential fear can be fully overcome, by traversing the final phase of the path. But first in the middle phase, the three forms of suffering mentioned earlier: anxiety, delusion, and disenchantment, need to be attenuated.

The memory of the insight into the Three Fundamental Characteristics (3C), together with the painful mind-states it triggered, creates a strong need to escape. This point is a significant milestone on the path, traditionally known as samvega, or ‘urgency’. It’s the visceral realization that one cannot return to life as it was before, without facing inner conflict.

The meditator may initially try to take an "emergency exit," attempting to return to a life centered around the illusion of a solid self. Sometimes this works, and a temporary sense of groundedness may reappear, but only for a while. The reason is that the insight into the 3C and the intuitive knowledge of their truth is too strong to suppress. The illusion no longer holds and the suffering returns, and with it, the sense of samvega renews itself.

As before, attenuation of suffering is not possible through direct effort or intention. It is a side effect of continued training, a gradual transformation rather than a deliberate escape. Potentially very useful are wishes, meant as intention, stating “May I be calm in the presence of suffering.” Still, the meditator often resists continuing the practice. This resistance becomes a self-reinforcing loop of existential suffering, centered around the same three mind-states.

This phase of the journey has been called the Dark Night, a term borrowed from St. John of the Cross. His Christian mystical path has been compared5 to the path of liberation in the Buddhadhamma.

Serene Confidence

At some moment the following may happen. The meditator, perhaps encouraged by a teacher or spiritual friend, feels a spark: “There must be a way out of this.” Experiencing this shift clearly, is known as the state of pasāda, often translated as ‘serene confidence’: a quiet, stable resolve to continue on the path. The transition6

Samvega → Pasāda

is a key turning point. This was the step the poet Rilke could not make, as described in the earlier post Motive. In order that this transition happens, the three skills need to be developed to a sufficient degree.

It is important to realize that this confidence is not the same as hope. Hope longs for the return of a lost sense of self and makes one wait. Serene confidence, by contrast, does not lead to waiting or yearning. It quietly says, without words: “Let us continue and see what will happen.”

Proceeding in this spirit leads the meditator toward a state of equanimity. It is a calm, balanced state, even in the presence of the Three Characteristics or other unsettling experiences. From this ground of equanimity, with suffering in the background, one may turn to the End Phase of the path.

End Phase

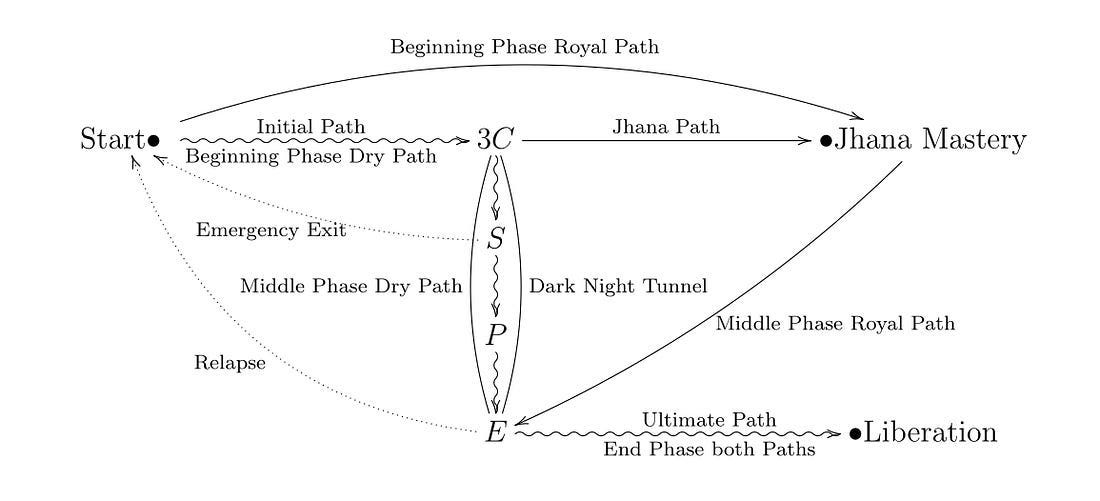

If the practice is not continued, then one may relapse to the beginning of the path, point B in Fig. 6.2. This is not a dramatic setback. In fact, returning from B to the equanimity point E a second time, is usually easier. It may even be beneficial, as it provides further experience with recognizing and relinquishing unwholesome habitual patterns.

The end phase runs along what was earlier called the ultimate path, that is motivated by transforming the self. The steps to be taken during this phase resemble those of the beginning phase: they involve the relinquishing of habits. But now, the goal is no longer to remove habitual loops in order to strengthen the self. It is to relinquish the underlying innate tendencies themselves, thereby transforming the self.

This presents a strategic difficulty. In the beginning phase, the patterns under investigation clearly caused suffering. According to the basic principle of avoiding pain, these patterns could be relinquished through the ego’s natural tendency to escape discomfort. But in the end phase, the work becomes more subtle. To uproot the basic tendencies, one cannot rely on those very tendencies themselves. It is like using a sword that can cut, but cannot cut itself; or an eye that sees, but cannot see itself. In the same way the ego, consisting of our basic tendencies, can be employed to relinquish certain patterns, but it cannot relinquish itself.

In a later post, specific practice strategies for this phase will be discussed. For now, it is enough to say that the key lies not in a direct attack on the self, but to use the cultivated skill of discipline, a steady, quiet willingness to let go, again and again.

The end of the path to liberation, at L, one has seen clearly that self and the world are virtual realities; one has also seen clearly that the natural aversion to this is caused by the misunderstanding that those VRs are real. Then there is no more belief in a substantial self, no more doubt, and no more belief that rituals are helping liberation. This is the first level of liberation (of a total of four); it is a partial liberation, but an important step.

In a book7 by Shaila Catherine, a beautiful description is given of the nature of a liberation, also known as awakening.

Awakening is a realization that is utterly unshakable; what’s more,

it occurs to no one, requires no confirmation, and attains nothing.

This refers to the state in which several or all tendencies causing mental loops with suffering have been fully relinquished.

Levels of liberation

After the first liberation step, called the first Magga (Path), there is more work to do. First of all, there are still potentially acting patterns, based on the tendencies just released. Relinquishing these is not hard. It is a matter of encountering their activity and disentangle them. When that has happened, one has reached the first Phala8 (Fruit). Secondly, there are still tendencies active, that have not yet been eradicated.

It would be ideal if the tendency to act on the basis of the pleasure principle were already eliminated at this point. But in reality the principal fundamental tendencies, desire, aversion, and ignorance still persist. There are good reasons why it is wholesome to transcend these tendencies. First, because conditions always change, so that it is simply not possible to live a life that avoids unpleasantness and clings to pleasure. Therefore as long as actions are driven by the pleasure principle, suffering will inevitably follow. Second, the pleasure principle reinforces a deep separation between self and others. When we desire something, we seek to possess it and exclude others from having it. This dynamic, based in competition, control, and protectionism, gives rise to an unwholesome society.

In contrast, unifying motivations, grounded in generosity, loving-kindness, and wisdom, create the conditions for true well-being, both individually and collectively. Yet, such noble ideals, taught by the Buddhadhamma and by Sunday school alike, are for beings conditioned by nature’s reward system a bridge too far to cross in a single liberation step. One needs to the path to liberation three more times to eradicate all innate tendencies, arriving at the fourth Magga. After that some patterns still may need to be relinquished in order to arrive at the fourth Phala.

In fact, the path toward transcending suffering unfolds in four distinct steps, as described earlier. These principal steps may be summarized as follows, by listing the relinquished tendencies.

Step 1: Wrong View, the belief that the self is a lasting, substantial entity.

Steps 2 and 3: Aversion and Sensual Desire, after first diluting them both.

Step 4: Conceit and Ignorance

Here, conceit translates the Pali word māna, which can be described as “wanting to remain as we think we are.” This goes beyond pride or arrogance. For example, believing that one will surely fail an exam might seem like humility, but it too is a form of māna. It is a self-image that conditions experience and behavior.

A More Complete Map

The previous map illustrated just one trajectory toward liberation, which sometimes is called the ‘Dry Path’. The meditators that follow it are called in the Visuddhimagga ‘the bare attention workers’. In the suttas a different path has been described, one that avoids the sharpness of the Dark Night Tunnel. As a sneak preview, we now present a more complete map, one that includes the Dry Path just described, as well as an additional trajectory: the 'Royal Path'. Following the latter trajectory, the three characteristics and the resulting states with suffering are still experienced, but more from a distance.

The dry path is accessible to most practitioners and offers direct insight into the challenges of practice, making it especially valuable for those who may want to teach others. The royal path, by contrast, requires a higher degree of concentration and is somewhat less easily available to practitioners, but is also less painful. However, those who reach liberation by this route may find it harder to guide others through the challenges of the dry path.

Nowadays part of a trip is called a ‘leg’. So the path to liberation can be said to have three legs.

Visuddhimagga, The Path of Purification (Buddhaghosa, translated by c. 400 AD), Chapter XX.

Also known as mind loop or habit loop. We often will simply use the word ‘loop’.

Congruent Spiritual Paths: Christian Carmelite and Theravadan Buddhist Vipassana, Mary Jo Meadow, Kevin Culligan, The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1987, Vol. 19, No.2.

In Christian mysticism, an experience similar to samvega is called cognitio vespertina: “it is getting dark”, while pasāda may be compared to cognitio matutina: “there is light at the end of the tunnel.” In both traditions, this transition is not achieved by willpower. Christian mystics speak of the need for divine grace. In the Buddhadhamma, similarly, one must be ‘ready’, the shift cannot be forced. In both traditions an intention to surrender does help.

Focused and Fearless, Shaila Catherine, Wisdom Publications U.S., 2008, p. 20.

The classical text Abhidhamma, and the Visuddhimagga that is based on it, both state that after each Path, the corresponding Fruit happens immediately after. In a paper by Kheminda Thera, Path, Fruit and Nibbana, 1965/1992, it is claimed, based on early Suttas, that this is not necessarily the case, but it happens later, latest when the body is decomposed (after death). We follow Kheminda’s view. The Abhidhamma view is consistent with the view of the early suttas, but not conversely. It could be the case that the meditation experience on which the Abhidhamma is based came from reports of advanced practitioners, that arriving at the Path, immediately were able to see through the patterns created by the eradicated tendencies.